Language of legislation, political climate have changed to boost its prospects

SHIRA SCHOENBERG – May 4, 2022

THE FIRST TIME a bill was proposed in Massachusetts to let immigrants without legal status obtain a driver’s license was in 2003. Since then, bills have regularly been introduced, languished in committee, and quietly been disposed of.

In February, the Massachusetts House for the first time passed a bill that would let this population get driver’s licenses, and the Senate is poised to follow suit on Thursday. While the legislation still faces procedural challenges, including getting a signature from a skeptical Republican governor, Charlie Baker, Democrats hold veto-proof majorities in the House and Senate, so the bill has a reasonable chance at becoming law. That raises the question of what exactly has changed over the last two decades.

Those involved say there are multiple factors. Immigrant organizations have been championing the bill for years, led in the early days by the Irish International Immigrant Center, Brazilian Worker Center, and the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, among others. But an expanded coalition co-led by labor unions took over the campaign in 2019 and has been more successful in its organizing. The national debate on immigration has also shifted. And the bill itself changed, with stricter provisions requiring immigrants to prove their identity. That has moved more law enforcement officials to back the bill, which in turn makes more legislators comfortable.

“Over the years, the momentum has built for the bill, and the coalitions have come together around it,” said Rep. Tricia Farley-Bouvier, a Pittsfield Democrat and long-time bill sponsor. “A lot of work’s been done to educate the general public about it.” The bill being considered by the Senate, similar to the bill that passed the House, would let an immigrant without legal status obtain a Massachusetts driver’s license after proving their identity, birth date, and Massachusetts residency. They would be required to submit two documents to prove their identity: a foreign passport or consular identification document, and one of five additional documents: a driver’s license from another state; US marriage or divorce certificate; birth certificate; foreign national identification card; or foreign driver’s license.

The Registry of Motor Vehicles would not create a record of applicants’ immigration status and could not share information with federal immigration officials. The RMV would work with the secretary of state to write rules to make sure no one who is not a US citizen is automatically registered to vote. The bill would go into effect July 1, 2023.

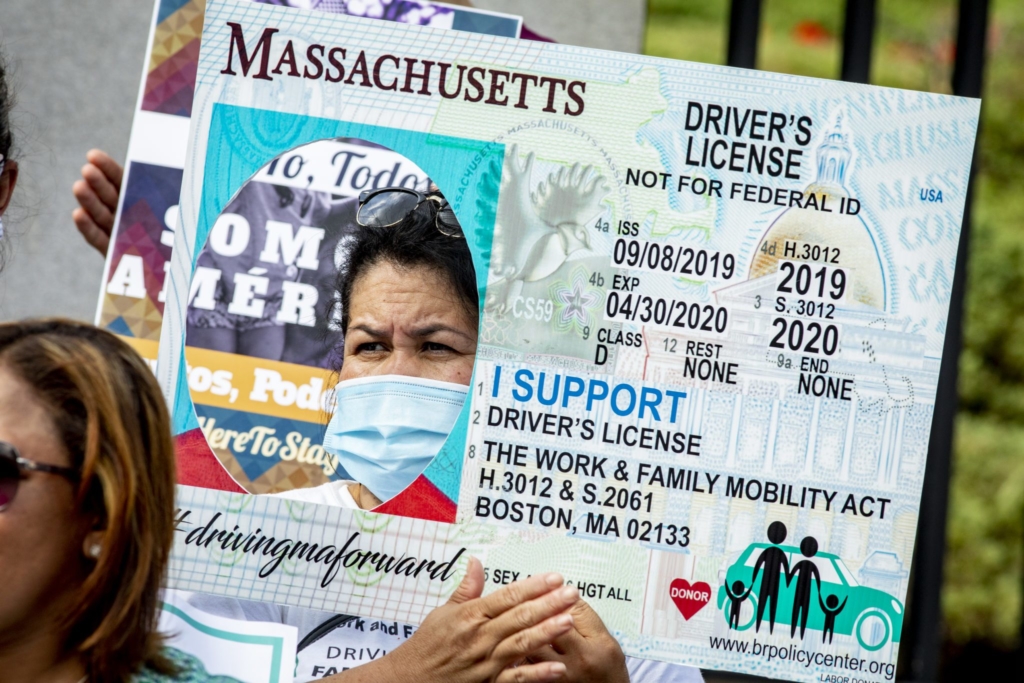

A Pass the Work and Family Mobility Act Rally was held on the steps of the Massachusetts State House on July 29, 2021. (Photo by Rose Lincoln)

Senate Transportation Committee chair Brendan Crighton, a Lynn Democrat and the bill’s lead sponsor, said earlier versions of the bill left it to the Registry of Motor Vehicles to determine what type of identification would be required. This time, advocates and legislators worked closely with law enforcement officials to develop a list of documents.

“There’s a common misnomer…that undocumented immigrants by nature do not have documents, so how do you know who they are?” Crighton said. “We took a deep dive into what types of ID requirements would work best in Massachusetts.”

Also new is the prohibition on the RMV keeping records of immigration status, which is meant to protect immigrants from having their information shared with the US government. Farley-Bouvier said that was added after seeing information-sharing happening in other states.

Crighton said lawmakers also added the section requiring that rules be written to prohibit accidental voter registration – a topic that has been Baker’s major concern.

Rep. Christine Barber, a Somerville Democrat who has championed the bill, said one key change in the state was Massachusetts’s decision in 2016 to implement the federal REAL ID requirements by creating two different driver’s licenses. Anyone can now get either a REAL ID, which requires stricter documentation and can be used for federal purposes like boarding an airplane, or a standard Massachusetts license, which can be used for driving and state identification. Under the legislation, the standard license would be given to immigrants without legal status. “Rather than having to create that in this state, we can use the system we have,” Barber said.

\Laura Rotolo, an ACLU attorney who has worked on the campaign for 15 years, said part of the earlier debate was whether to use the standard Massachusetts license or create a new license for undocumented immigrants. Having the state create a two-tier system due to REAL ID made it technically easier to use the standard license without worrying about federal requirements.

Amy Grunder, director of state policy and legislative affairs for the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, said national factors have made the bill more palatable as well. There are 16 states that now give driver’s licenses to immigrants without legal status. A handful of states started providing them in the 1990s or early 2000s, but the vast majority started in the past decade. “There’s national momentum,” Grunder said.

Another factor is former president Donald Trump’s public animus toward illegal immigration. “The Trump administration, with its attacks on the immigrant community, really raised the profile of our state’s immigrant community and the concerns and needs of this community before the general public,” Grunder said.

Both Rotolo and Grunder said the pandemic also called attention to the importance of immigrants without legal status, many of whom continued working during the lockdowns in essential jobs like restaurant work or home health care. “They stocked our shelves, made sure our hospitals were clean,” Rotolo said.

Perhaps the biggest shift has been in the advocacy surrounding the bill. While hundreds of bills are filed each year, the ones that pass are often those with powerful backers who raise public and legislative awareness. Immigrant advocacy groups had been pushing for the bill for years, but in 2018, the Brazilian Worker Center joined with the Service Employees International Union to create the Driving Families Forward Coalition. The inclusion of the politically powerful labor union galvanized the organizing effort, and the coalition ultimately got support from 270 organizations.

“We joined unions, worker centers, community-based organizations, faith organizations, businesses, and law enforcement,” said Lenita Reason, executive director of the Brazilian Worker Center.

In particular, Reason said the expanded organizing led to closer engagement with law enforcement. The coalition sat down with Chelsea Police Chief Brian Kyes, president of the Massachusetts Major City Chiefs Association, to figure out what documentation the police were comfortable relying on for someone to get a license. As a result, the Major City Chiefs group endorsed the bill for the first time. The coalition also obtained support from some of the state’s more liberal-leaning sheriffs and district attorneys.

Middlesex County Sheriff Peter Koutoujian, for example, said in a statement that the bill will improve public safety and lower insurance costs – since more drivers will be insured and the police will know who drivers are – while giving immigrants easier access to jobs, medical appointments, and schools.

Lawrence Police Chief Roy Vasque said with past versions of the bill, identification had been the main sticking point preventing law enforcement officers from supporting it. “From the law enforcement standpoint, it was really about the ID and making sure that’s as tight as it could possibly be,” Vasque said. “We were concerned about giving bad guys an opportunity to change their identification and continue doing wrong.”

The Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association, which represents a broader swath of chiefs, does not support the bill. But Vasque said the Major City Chiefs decided to take that step because many of them are dealing with undocumented immigrants in their community and understand the reasoning behind the legislation. “Law enforcement wants to know who our officers are stopping,” Vasque said. “And hopefully they stop now that they’re not worried about running from law enforcement because they have an ID.”

Farley-Bouvier called the organizing, and particularly the support from law enforcement, a “game-changer” in moving the bill forward.

Public opinion has also shifted, though it remains split. A 2006 poll done by the Suffolk University Political Research Center asked whether undocumented immigrants should be issued drivers licenses, and 67 percent of respondents said no, while only 25 percent said yes. A Suffolk University/Boston Globe poll released May 1 found public opinion is now evenly split, with 47 percent opposing giving undocumented immigrants driver’s licenses and 46 percent supporting it.

David Paleologos, director of the Suffolk University Political Research Center, said over that time, “The demographics have changed in Massachusetts and the polarization has changed as well.” He said the groups more likely to support granting driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants – younger people, women, and Black and Latino residents – are taking more active roles in politics.

That said, opposition still exists. The House vote was 120-36, with all the chamber’s Republicans opposing the bill. Baker has long maintained that licensed drivers should have “lawful presence” in the US. Addressing the current version of the bill, Baker has raised particular concerns about whether immigrants without legal status could be accidentally registered to vote.

John Thompson of the Massachusetts Coalition for Immigration Reform, which supports restricting immigration, said the core argument against giving immigrants here illegally driver’s licenses remains the same: “We should not be condoning people entering the country and remaining here unlawfully,” Thompson said. “It’s an affront to the rule of law, and it’s bad economically and in terms of public safety.”

Republican gubernatorial candidate Geoff Diehl recently held a press conference with a woman whose son was a killed by an undocumented immigrant driver, where he argued that the bill could create a flood of migrants to the state.

Some Republicans are getting behind an amendment proposed by Senate Minority Leader Bruce Tarr, a Gloucester Republican, which would give immigrants without legal status a “driver’s privilege card” that is different from a license, which would let them drive but alleviate concerns about accidental voter registration.

Anthony Amore, a Republican candidate for state auditor who previously worked as an immigration inspector at Logan Airport, said the changes to the bill related to identification do not assuage his concerns, since RMV officials are unlikely to be able to accurately identify foreign documents that are real versus those that are fraudulent. “I worked for immigration services for five years, and I couldn’t tell you what an authentic birth certificate from Reykjavik looks like,” Amore said. “The people they’re presenting it to will have absolutely no way of knowing whether that document is authentic.”